IMPERIAL BEACH, Calif. — At a time of tumult over immigration, with illegal workers routed from businesses, record levels of deportations, border walls getting taller and longer, Friendship Park here has stood out as a spot where international neighbors can chat easily over the fence.

Or through it, anyway. Families and friends, some of them unable to cross the border because of legal or immigration trouble, exchange kisses, tamales and news through small gaps in the tattered chain-link fence. Yoga and salsa dancing, communion rites, protest and quiet reflection all transpire in the shadow of a stone obelisk commemorating the area where Mexican and American surveyors began demarcating the border nearly 160 years ago after the war between the countries.

“It’s hard to see each other, to touch,” said Manuel Meza, an American citizen sharing coffee and lunch through the fence with his wife, who was deported and now drives three hours for regular visits at the fence. “It’s strange, but our love is stronger than the fence.”

But in a sign of changing times, new border fencing that the Department of Homeland Security is counting on to help curtail illegal crossings and attacks on Border Patrol agents will slice through the park, limiting access to the monument and fence-side socializing.

In addition to the fence, a second, steel mesh barrier will line the border several yards on the United States side, creating a no-man’s land intended to slow or stop crossings.

With construction expected to begin early next month, the federal and state governments are still negotiating how to provide some access to the monument. But more than a few San Diegans see a paradox in an area meant to celebrate friendship taking on tones of distance and separation. Pat Nixon, the former first lady, at a dedication here in 1971, declared, “I hate to see a fence anywhere” as she stepped into Mexico to shake hands.

“It’s harmful to the kind of family culture we have at the border,” said United States Representative Bob Filner, a Democrat who represents the area and who has urged the department not to build in the park. “We have a friendly country at the border. We have family ties across the border. It is one place, certainly in San Diego, where we talk about friendship at the border.”

But Border Patrol officials, who regularly post agents there, said the park had an underside.

Although much activity may be innocent, smugglers have taken advantage by passing drugs and contraband through openings. People have even tried to pass babies through ragged metal slats that mark the border on the beach, said Michael J. Fisher, the chief patrol agent in San Diego. The agency now operates a checkpoint to screen people leaving the park.

“It’s a real shame,” Mr. Fisher said, gazing down on the beach as a young boy at play darted briefly into the United States from Tijuana. “It is a nice area with the historical marker. Having people meet and mingle is good. But unfortunately, any time you have an area that is open, the criminal organizations are going to exploit that.”

“We cannot,” he added, “have it open, not at the expense of reducing the ability to patrol the border.”

The new fencing is part of a 14-mile project to reinforce and build new barriers from the ocean to areas east of the Otay Mesa port of entry.

The project includes filling in a deep valley known as Smuggler’s Gulch, a notorious crossing point just east of the park, with tons of dirt, to the dismay of environmentalists.

Unlike the trend in the past year or two along most of the 2,000-mile Southwest border, Mr. Fisher said illegal crossings had increased in the San Diego area, along with attacks on agents who encounter smugglers raining stones and other objects on them and their trucks. One-fourth of all such assaults, he said, occur in the San Diego sector, which more than a decade ago was one of the hottest spots for illegal crossings.

While a flood of new agents and bolstered fencing has pushed much of the crossings to the eastern deserts and the sea, where smuggling by boat is a growing problem, people still regularly climb over, tunnel under or cut through the fence, sometimes with blow torches and sophisticated cutting tools.

But critics of the plan to extend the fencing in Friendship Park said the Border Patrol had exaggerated problems there, one of a smattering of spots along the border where new fencing has dampened cross-border bonhomie.

Naco, Arizona, no longer plays an annual volleyball game across the fence because the ragged wire one has been replaced by a taller barrier of solid plates. Residents of Jacumba, Calif., and Jacume, Mexico, who once freely crossed back and forth, complain that reinforced fencing has severed generation-long ties.

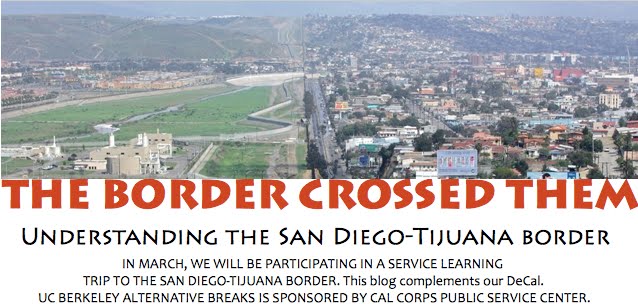

But Friendship Park, part of the surrounding Border Field State Park, had come to symbolize the tight embrace of San Diego and Tijuana, the border’s biggest cities.

Already, construction of the new fence has cut off a long stretch of the old fence. But on a recent Sunday, a steady stream of people came to greet friends and relatives there.

Jacqueline Huerta pressed her face against the fence on the Tijuana side to get her first look at her 4-month-old niece, Yisell.

“Oh, how cute you are,” she exclaimed, forcing her hand through an opening to caress the baby’s hair.

“Where else can she do that?” said her mother, Socorro Estrada, who drove six hours from Bakersfield, Calif., with family members to the fence. The baby’s father said he was on probation and could not leave the country and, in any case, the baby’s grandmother had advised them against traveling into Mexico with such a young infant.

Nearby, the Rev. John Fanestil, a United Methodist minister, offered his weekly communion through the fence, passing the wafer through a hole to a small gathering on the Mexican side. (Technically, that was a customs violation, but Border Patrol agents nearby tolerate most casual contact.)

“Arresting a clergy person for passing a communion wafer through the fence would be a public relations nightmare for them,” Mr. Fanestil said with a smile just before beginning.

Juventino Martin Gonzalez, 40, accepted the wafer. He had been deported to Mexico a month ago after living and working in the United States for 20 years, fathering three children, now teen-agers, here.

He came, he said, for a glimpse of the American side he still considers home.

“It is hard because I was the one paying the rent,” he said. “I belong over there, not here. But until then, this is the closest I can get but it is not close enough for them.”